Unsafe Sandwich: The 2017 Hohenlimburg (Germany) Level Crossing Collision

Background

Hohenlimburg is a suburb of 29245 people (as of 2013) belonging to the city of Hagen, located in the federal state of North-Rhine Westphalia 21km/13mi south of Dortmund and 63km/39mi northeast of Cologne (both measurements in linear distance).

Hohenlimburg lies on the Ruhr-Sieg Railway, a 106km/66mi double-tracked electrified mainline. Opening between 1859 and 1861 makes the Railway one of Germany’s oldest railway lines. The line was originally built to transport coal to steel-plants, but is nowadays used for everything from regional passenger service to express services and freight trains. Despite featuring numerous turns and tunnels some sections of the line are so steep that heavier trains, especially freight services, require to be pushed up certain sections by a second locomotive at the back. Some sections are limited to as little as 80kph/49mph while others allow as much as 120kph/75mph.

The vehicles involved

DGV 93590 was a freight service from Hohenlimburg to Hagen’s freight yard consisting of 26 two-axle low-wall flatbed cars carrying gravel intended as ballast for new railroad tracks. Two small diesel locomotives were moving the train, with one being coupled to either end. The locomotives were former DB series 365, now owned by a leasing-company and leased to Die-Lei, a company specializing in railway line construction and maintenance. The series 365 had been introduced in 1955 as the DB V60 as a small shunting-locomotive intended to help retire steam locomotives from the job. Various companies cooperated on the development and construction of the type, with the two locomotives involved in the accident being made by MaK in the early 1960s and serving with the DB until the late 2000s. Each series 365 measures 10.45m/34ft in length at a weight of 49 metric tons. They have three axles driven by connecting rods similar to a steam locomotive. The locomotives involved in the accident were equipped with a remote control system, allowing them to be driven without the driver needing to be in the cab.

Crossing the train’s path at a level crossing just east of Hohenlimburg station was a Mark 1 Citroen Berlingo, a small two-door panel van measuring 4.13m in length at a weight of 1.25 metric tons.

The accident

DGV 93590 was scheduled to depart Hohenlimburg station eastbound at 21:15 on the 17th of July 2017. The train was configured in a so-called sandwich-setup, with one locomotive on either end of the train cars. In Germany multi-tractions only work automatically if the locomotives are directly connected by wires (while some other places like the US use wireless remote-control systems), so with the freight cars between the two locomotives of DGV 93590 both locomotives carried a driver who was communicating with their colleague at the opposite end of the train. As a drawback this strategy allows for a slight desynchronisation between the two locomotives.

The train split in two almost immediately after starting to move, with cars 16 and 17 not being connected to each other in any way. It’s unknown if the two halves of the train accelerated at different speeds or if the rear half started moving a moment later than the first. Either way, as both parts picked up speed the gap between them started to grow. The dispatcher allowing departure of the train started the closing-sequence of a level crossing 1.2km/3900ft from where the train had started, turning on the crossing’s warning lights, horn and causing the barriers to lower. This forced a craftsman in his Berlingo to wait for the train to pass. A sensor ahead of the crossing counted the wheels passing over it, a second sensor just past the crossing did the same. Registering the same amount of axles having “entered” and “departed” allowed the level crossing to open after the leading part of the train had passed through. The Berlingo started to drive into the seemingly clear crossing, just to be struck on the rear right hand corner by car 17 of the freight train. The train flung the car around as it pushed it out of the crossing, with the driver in the rear locomotive spotting the damaged car being pushed out of the train’s path.

Spotting the accident and realizing what had happened led the rear driver to radio the one in the leading locomotive, telling him to stop immediately as the train had come apart and hit a car. This came after the dispatcher had already realized the separation of the train and ordered an emergency stop, causing the rear half of the train to crash into the already stopped leading half while the drivers were still talking to each other. Car 16 and 17 collided at one level, jolting the train forwards, but car 20 dug beneath car 19, throwing it to the right. The driver of the Berlingo had suffered minor injuries in the accident, with everyone else remaining unharmed. Damages to the train, tracks and car were listed at 27500€/29000$.

Aftermath

It became clear rather fast that no technical fault had caused either of the three incidents (separation, car-train-collision, rear-ending collision of the train-halves) but that human error was at the root of the night’s events. All train cars and locomotives involved had been in perfect working order, so something must have gone wrong during preparation of the train at Hohenlimburg station. Preparing DGV 93590 was the responsibility of the shunting assistant. Preparing a train usually involved ensuring that all train cars and locomotives are properly coupled together, hooking up all pneumatic lines for the brakes and opening the valves so the system could be pressurized. Opposite to a car a train’s brakes apply when pressure drops, so an improper connection or pressurization should cause an automatic application of the brakes and keep the train from moving.

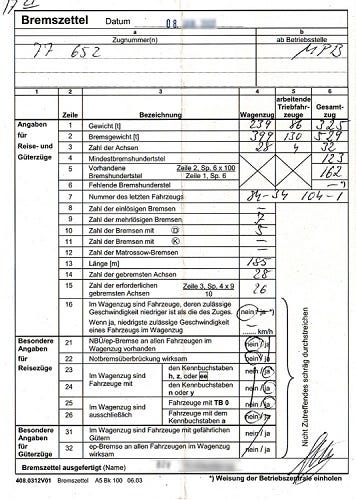

During preparation of the train a “brake slip” is filled out, a pre-printed form containing various information about the train’s size, weight with and without locomotives, braking-power, axles and then some. The filled out form is then handed to the train driver of the main/leading locomotive so he can adjust the locomotive’s brake-system accordingly. Following the accident investigators confiscated the form with the data for DGV 93590, and immediately found several errors with it.

As a main error, the form listed the train as having 27 cars at a total length of 467m/1532ft with 75 axles, weighing 1426 metric tons. In reality the train had 26 cars with a total of 84 axles and measured 456m/1496ft at a weight of 1372 metric tons. Due to this basic information being wrong all further data calculated from it was also false.

Looking past the more or less worthless form investigators looked at the next step of the process, the ensuring of proper connection of the pneumatic lines and couplers throughout the train. And again, the shunting assistant had failed to properly do his job. He had failed to notice that car 16 and 17 had been completely disconnected from the start, and the rear freight car had been coupled to the rear locomotive, but the pneumatic lines had not been connected. The closed valves on cars 16, 17 and 26 were also not noticed. Had these valves been opened the air would have escaped from the system, applying the brakes and keeping the train from departing. The train had been assembled at Hohenlimburg station, with the rear freight cars being brought in and then parked with their system still charged and the pneumatic brakes released, having only the additional parking brake hold them in place. As such the pneumatic brakes remained deactivated as no-one had opened the valves after assembling the train.

Due to the train being assembled at the station guidelines demanded a full check of the brake-system ahead of departure, which involves inspecting the condition of all brakes and testing their function. The shunting assistant was responsible for this as well, and, given the situation that ended up presenting itself, clearly had not properly done his job. According to his own statement and that by the driver in the leading locomotive he did order the driver to apply and release the brakes, but clearly failed to actually examine all the brakes as he would have most certainly noticed the brakes from car 17 back not applying. Regardless of this the driver in the leading locomotive was handed the brake-slip and told that all brakes were working fine, making the driver conclude that the train was ready for departure.

The report also notes that three different configurations for the train were listed in official paperwork. Originally the train was listed as weighing 800 metric tons at a length of 350m/1148ft with a single locomotive. This was the train scheduled for the day. The actual train was 600 metric tons heavier, significantly longer, and had a second locomotive push from the back. And then the actual physical train differed from the train listed in the brake-slip. Even without the latter discrepancy the train was “invalid” and the driver in the leading locomotive, who had documentation showing the old and actual configuration, should have never reported the train “ready” to the dispatcher.

Lastly, investigators noticed that the leading locomotive’s signaling system component was inactive and had been turned off for at least the last couple of days ahead of the accident, making it technically illegal to use for trains outside shunting-operations. It was turned on when the locomotive was examined by the investigators, but the data-logger showed that it had been turned off until two minutes after the accident. This had no effect on the accident at hand, but it did match the gradually emerging image that the construction company was rather negligent in their operation.

In the end the investigation couldn’t determine with certainty who had failed to connect the pneumatic lines, just that the shunting assistant had failed to notice the missing connection and the open coupler, along with the rear train driver failing to ensure proper function of his brakes, which would have led him to notice the disconnected pneumatic line between the rear freight car and rear locomotive. As such neither he or the shunting worker could be blamed severely and certainly enough, and neither faced legal consequences for their actions. It’s unknown if they kept their jobs.

The report notes that since 2012 there had been three train-accidents where DIE-LEI had acted in gross negligence, with all three accidents happening to trains with their signaling system components turned off. Each time they had been instructed to ensure it wouldn’t happen again, and yet it had always happened again. Following this fourth accident the federal railway ministry (EBA) revoked the company’s permit to operate trains in Germany in August 2017. As of this piece being written (December 2022) they seem to have improved their operational safety enough to regain the permit.

Dozens of the old V 60 are still in commercial service throughout Europe, mostly by private rail service providers. Their age, availability and simplicity has also made the popular as a reliable workhorse for enthusiast groups offering historic train tours. DIE-Lei currently lists no former series 365 as part of their fleet.

_______________________________________________________________

A kind reader has started posting the installments on reddit for me, I cannot interact with you there but I will read the feedback and corrections. You can find the post right here.