Opening a Gate to Hell: The 1989 San Bernardino (USA) Derailment & Pipeline Fire

Background

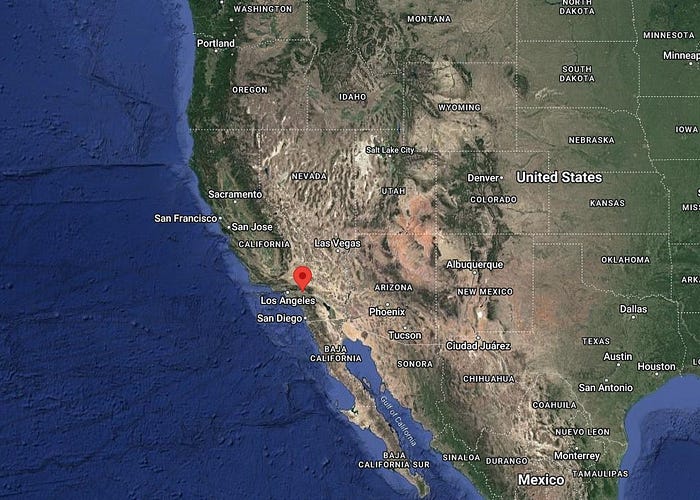

San Bernardino is a city of 222101 people (as of 2020) in the extreme southwest of the USA, located in the federal state of California 82km/51mi east of Los Angeles and 158km/98mi north of San Diego (both measurements in linear distance).

San Bernardino lies on the southern side of Cajon Pass, a 1151m/3777ft mountain range separating San Bernardino valley from Victor Valley. The pass is navigated by several roads and a rail line which opened in 1880 for the California Southern Railroad, a subsidiary of the Santa Fe Railway. The now three-tracked rail line over the pass has gradients of up to 3% and is limited to 113kph/70mph in the flatter sections while trains travel up the steeper sections at 23–35kph/14–22mph and down them at up to 48kph/30mph. The pass is mostly used by freight trains, one of the exceptions being Amtrak’s “Southwest Chief” travelling daily between Chicago and Los Angeles.

Running alongside the tracks as they pass through the Muscoy-neighborhood of San Bernardino is a 35.5cm/14in high pressure petroleum pipeline, located six feet below the surface. Called the Calnev Pipeline it connects Nellis Air Force Base in Las Vegas, Nevada with Los Angeles at a length of 890km/550mi, carrying up to 128 thousand barrels (1 barrel is 159l/42gal) per day.

The train involved

SP MJLBP1–11 was a freight train carrying trona, a mined mineral used to produce sodium carbonate. As usual for freight trains the train contained several locomotives on either end. Leading the train was SP (Southern Pacific) SP 8278, followed by SP 7551, SP 7549 and SP 9340. Following the four “head” locomotives were 69 four-axle hopper cars capable of carrying 100 metric tons each, with two more “helper” locomotives (SP 8317 and SP 7443) forming the rear of the train. The leading locomotive and one of the helpers were EMD SD40T-2 units, a six-axle diesel-electric locomotive introduced in 1974. Measuring 21.54m/71ft at a weight of 167 metric tons each of these locomotives, nicknamed “Tunnel Motors”, has a power-output of 2240kW/3000hp from a V16 diesel engine.

Locomotives #7551, #7549 and #7443 were EMD SD45R-units, a more powerful version of the SD40’s platform introduced in 1965. They share the same size and weight, but have a power output of 2680kW/3600hp as they are powered by a V20 diesel engine instead of a sixteen cylinder unit. SD 7551, the second locomotive in the train, is notable for wearing a new yellow-red livery in anticipation of Southern Pacific’s merger with the Santa Fe Railway, an undertaking that never became reality.

The last locomotive in the train, running in fourth place at the head of the train was SP #9340, an EMD SD45T-2. Intended as an upgrade over the problematic SD45 the SD45T-2 was introduced in 1972, featuring improved electronics, new bogies and (marked by the “T”) cooling system upgrades after Southern Pacific had encountered repeated overheating-issues on some routes in the western USA. They are identical to the SD45s they are based on, with only minor visual differences giving away the upgrade.

The accident

In early May 1989 SP was contracted to move 6900 metric tons of trona to the Port of Los Angeles, where it would be loaded onto a ship headed for Colombia. Lake Minerals, the mining company selling the mineral, had rented 69 100-ton hopper cars from SP and the Denver & Rio Grande Western Rail Road, which were collected and loaded at Rosamond, approximately 115km/71.5mi linear distance from San Bernardino. As loading completed the mining company handed the final paperwork to the clerk (Mister Blair) for processing, leaving the “loaded weight” part empty. A later statement would say that they assumed the railway company would know that they obviously loaded the hoppers to capacity. However, Mister Blair entered the loaded weight as 60 metric tons per hopper car, going by a visual comparison of the quantity to that of 100 metric tons of coal. As a result the paperwork for the train listed a weight of 6151 metric tons total (2011 from the freight cars, the rest from the cargo), well below the actual weight. This false data would be what the configuration and operation of the train would be organized by.

On the 11th of May at approximately 10pm train driver Frank Holland (age 33), conductor Everett Crown (age 35) and brakeman Allan Riess (age 43) arrived at Mojave to take command of three locomotives (SP 7551, SP 7549 and SP 9340) intended for the waiting trona shipment. When the intended leading unit’s motors refused to fire up the crew was instructed to add SP 8278 to the front of the train, but to keep the faulty locomotive (#7551) as part of the train, running it “cold” (like a train-car). The crew departed Mojave at 12:15am on May 12, heading to Fleta to pick up the freight cars, returning to Mojave to move the locomotives to the other end of the train and then finally taking the train to Palmdale to meet up with a helper locomotive, meant to be attached to the back of the train to help slow the descend down Cajon Pass.

In the meantime a shift change had occurred at the dispatch-offices, with the new dispatcher correctly recalculating the weight of the train to be around 8900 metric tons, based on previous experience with these shipments. At a 2.2% downhill grade a locomotive’s dynamic brakes (using the motors as generators to slow the train) can hold a load of 1800 metric tons at 40kph/25mph. The dynamic brakes are most effective at this speed, diminishing if the train is going slower or faster, which is why train crews tend to try and stay close to that speed on steep downhill tracks. The dispatcher calculated that the dynamic brakes of 5.23 locomotives (so, 6) were needed to keep the trona-train under control. As such the plan of picking up a single helper locomotive was scrapped in favor of calling in 2 helpers from West Colton. Fatally, he had not been notified of the disabled dynamic brakes on #7551. Furthermore, unbeknownst to everyone, #7551 wasn’t the only locomotive with faulty brakes. Also, Mister Holland was not notified that the train weight listed in his paperwork was wrong, so he assumed that five locomotives with full dynamic brakes were more than sufficient.

The hopper cars and #7551 were only braking with their pneumatic brakes, which slow down by pressing metal “shoes” against the running-surface of the wheels, trading speed for heat. Due to the involved temperatures these brakes work best below 40kph/25mph and when used sporadically, as their effectiveness is reduced the hotter they get. Even with all six locomotives having full dynamic brakes the train would’ve had to make use of the pneumatic brakes on top of the dynamic brakes, ensuring a safe descend. With one locomotive “down” the pneumatic brakes were crucial.

At approximately 2:30am train driver Lawrence Hill and brakeman Robert Waterbury (acting as a “lookout”) boarded a pair of locomotives (#7443 and #8317), being scheduled to help push a northbound train up the hill to Oban before helping the trona-train back down from there to West Colton.

At approximately 7:15am the train crested the beginning of the downhill grade near Hiland, starting the descend down the southern side of Cajon Pass. Almost immediately the train’s speed exceeded 40kph/25mph, with Mister Holland realizing that he had an unusually hard time controlling the speed of the train. He tried his best with the dynamic braking he had as well as the pneumatic brakes, trying not to overheat them too fast, and radioed back to the helper locomotives to do the same. With the men’s efforts seeming increasingly useless Mister Hill, in desperation, triggered an emergency stop. However, this meant cutting the engines, which disabled any dynamic braking the train had had. The train’s data-logger went past it’s 145kph/90mph limit as the train ran out of control, with the pneumatic brakes starting to melt from excessive heat. In reality, the train had been doomed the moment it entered the grade.

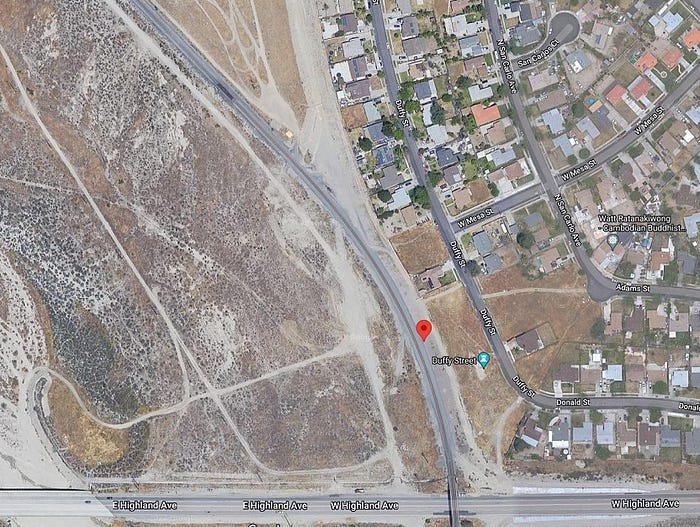

At 7:36am the train entered a four-degree left hand turn a short distance north of Highland Avenue. The turn was limited to 64kph/40mph, but calculations later showed that the freight train was travelling at 177kph/110mph and immediately derailed. The leading locomotives fell over as they plowed through 7 of the eight residential houses on the western side of Duffy Street, with the rest of the train, including the helper-locomotives, piling up behind them. Mister Riess, Mister Crown and 2 children (aged 7 and 9) who lived in the houses died, 4 residents and the remaining 3 members of the train-crew were injured. The derailment left the site covered in bits of trains and houses as well as a thick layer of trona, looking almost like snow in some photos.

Aftermath of the crash

One of the residents, 56 years old Early Davis, later recalled sitting in her living room with the newspaper when the ground started shaking. Several newspapers at the time had predicted “the big one”, a massive earth quake supposedly soon hitting the area. Instead, as she looked out the window, she saw the train go straight instead of following the curved track, obliterating the house of her neighbor Mister Shaw. The residential homes had little to offer against over 9000 tons of steel coming for them, with the resistance from the locomotives digging into the ground doing more to slow them than the collision with several houses did.

Responders were on site in minutes, but due to the instability of the piling wreckage they were hesitant to bring in heavy equipment for the rescue, fearing it could collapse survival spaces inside the remains of the houses. Instead the wreckage was combed through piece by piece, largely by hand. It took fifteen hours to free Mister Shaw, who survived with a broken pelvis, and several more hours until every resident was accounted for, most of them, fortunately, alive. Up in the leading locomotive Mister Holland had remained in his seat the whole time, surviving most of his locomotive being destroyed with (one might say “just”) a punctured lung and several broken ribs. He managed to climb out of the wreckage and was discovered by nearby residents who got him to an ambulance.

With all residents accounted for heavy equipment was brought in to clear the wreckage as well as remove the remains of the destroyed houses and all the spilled trona. During this part of the process the pipeline’s position was marked by stakes, however, the officials from the pipeline’s operator chose not to stick around once the rail cars were removed, leaving workers to be careful enough when removing copious amounts of the mineral. The pipeline had been shut off after the accident, but with no sign of a leak and high pressure on officials to resume operation of the pipeline it was reopened early into the recovery-process.

The fire

On the sixteenth of May, the same day rail service on the repaired track was resumed, an excavator was brought in to remove the trona spilled all over the place. The process took until the 19th, at which point the excavator was withdrawn and cleanup declared finished. Calnev had elected to only inspect certain points along the pipeline during the recovery-effort, rather than excavating it in full along the site of the accident or conducting a pressure-test after cleanup was completely done, not wanting to wait as long in the case of the latter option. The cleanup of the spilled cargo left the pipeline under as little as 60cm/2ft of soil, much less than it had originally been.

Unbeknownst to anyone involved the backhoe used to collect the spilled cargo had caused several gashes in the pipeline, which weakened the pipeline past the point where it could withstand the pressure inside it (estimated at 1600psi). On the 25th of May 1989, 13 days after the accident, the pipeline failed at just after 8am. Witnesses looking northwest from city hall saw what looked like a nuclear bomb going off in the distance. A fatal rupture in the pipeline had sprayed fuel several feet into the air, essentially turning it into a vapor. The cloud of fuel and air found a spark (it was later theorized to be a water heater), and at once the whole street went up in flames, having been turned into the inside of a combustion engine. Fire crews managed to save a few houses at the start, but as more and more units arrived and hooked up their hoses water pressure fell off a cliff, with Muscoy having had insufficient water pressure to begin with. Within minutes the firefighters could do little but watch the houses burn. By the time they locked down Highland Avenue and ran hoses across it to stronger hydrants it was too late.

The rupture was noticed in a control room for the pipeline, but not only were workers hesitant to act on the drop in pressure but once they acted on the alert a valve downstream of the rupture failed to close, allowing fuel to flow back down the Cajon Pass, further feeding the fire as the supply from upstream was cut. The fire burned for almost seven hours before running out of material, destroying eleven houses (among them the one spared by the derailing train), burning 21 cars and killing two residents.

Aftermath

Once the fire was out further pieces of the train were found along the pipeline, showing just how much of a patchy job had been done inspecting the pipeline. Surviving residents showed open anger at the pipeline’s operator and city officials, saying that their lives and livelihoods were valued below fuel for Las Vegas and that the cleanup had been rushed because of that.

In the meantime the NTSB continued its investigation of the derailment that started the process, further examining the remains of the trains. Back when they had first examined the wreckage at the site (12 hours after the derailment) they found several wheels sitting improperly on their axles (which they are heat-shrunk onto), concluding that the pneumatic brakes had been used excessively to the point of the ensuing heat expanding the steel wheels so much that they no longer sat attached to the axles. The data-logger recovered from SP #7549 (the third locomotive) showed that that locomotive’s motors worked just fine in propulsion-mode, but when used for dynamic braking they fell completely flat. The following locomotive, #9340, had the dynamic brakes cut in and out at random times, functioning sporadically which meant they were of limited use. The cause for this, similar to #7549’s defect, was never determined.

With the rear of the two helper-locomotives (#8317) also being without functioning dynamic brakes this left just two out of six locomotives at full braking-capability. Mister Holland was only aware of one locomotive’s brakes being faulty, but calculated that he had sufficient braking-power for the weight of the train. Tragically he got that weight from the cargo manifest, which listed the faulty weight of 6515 metric tons instead of approximately 8900 metric tons. In reality, he was far from having sufficient braking for either value.

The NTSB’s investigators recalculated the train’s journey with the true condition and weight of the train and concluded that the crew could have regained control and stopped the train with the brakes they had available, if they had crested the begin of the downhill track at no more than 24kph/15mph. However, they didn’t know that they had a heavier train and faulty brakes on most of their locomotives, so one cannot blame the train crew for not (essentially randomly) choosing to begin their way down the Pass well below the usual target speed (which is chosen for the efficiency of the dynamic brakes). Furthermore, it was discovered that Southern Pacific’s driver training didn’t include any material on regaining control of a runaway train, with their mountainous routes and the trains running on them also lacking oversight, likely contributing to the train’s faulty brake-system being overlooked. Ensuring proper function of a train’s brakes is always important, but should be of special importance when the train is meant to navigate steep downhill routes.

The investigation concluded that the derailment was the result of a chain of unfortunate circumstances, major players being the improper creation of the cargo’s paperwork and most of the various locomotives that happened to be combined for the train having faulty brakes. By the time the train started its way down Cajon Pass the derailment was inevitable no matter what the train crew did. In truth, their best option might have been to bail out, although even at the start of the grade this could have led to severe, if not lethal, injuries.

Besides the death and destruction residents soon fell victim to a catastrophe in human form. The fire wasn’t even quite out when a lawyer showed up on Duffy Street, one of the ambulance chasing variety. He promised the affected residents compensation and riches, inviting a number of them to a party at his home, showing off his apparent success. When a settlement came in the lawyer took the money and ran, with some claiming he went all the way to Spain, leaving the residents with nothing. To add insult to injury Bob Holcomb, the city’s mayor at the time, negotiated a deal with Southern Pacific to get each victim 5000 USD (11440 USD/10397 Euros today) without needing to go through a lengthy trial. Some of the involved residents collected government aid, which was cut off when the 5000 USD were counted as income.

Southern Pacific agreed to pay all moving, storage and temporary housing costs for displaced residents as well as purchase the eleven homes damaged or destroyed in the derailment. They also agreed to reimburse the City of San Bernardino for all expenses incurred in response to the accident, as well as any claims against the city resulting from the accident.

Attempts to keep the Calnev-Pipeline from being used again were unsuccessful, and so a number of residents chose to take settlements from Southern Pacific and/or Calnev and moved away rather than rebuilding. The properties closest to the tracks were rezoned as open space, keeping them as a safe-zone should another derailment take place. A lot of other plots sat empty for years, but by 2016 at least three houses have been rebuilt in the area where the derailment and fire had taken place. Southern Pacific changed their cargo-handling guidelines, instructing clerks to assume any freight car which doesn’t have a listed weight when the paperwork is handed in to be loaded to capacity. This way a train can be lighter than claimed but never heavier, ensuring a sufficient number of locomotives is assigned. This, of course, assumes that a tragic grouping of several faulty locomotives won’t happen again. Seven years after the accident Southern Pacific was bought up by Union Pacific, who still run trains past the site of the derailment.

The four leading locomotives, along with all 69 hopper cars were destroyed in the derailment. They were sold to Precision National for spares and scrap value and cut up at the site. The rear helper-locomotive (#8317) was also sold to Precision National, but was repaired and sold to a leasing-company. It was spotted running for Union Pacific as late as 2005. Locomotive #7443, the leading helper-locomotive, was repaired and returned to service with Southern Pacific, moving to Union Pacific after their merger and being finally retired from US service in 2000. It was bought by the National Railway Equipment Company and rebuilt with different gauge bogies for MRS Logistica. It was spotted in service with the Brazilian company in 2019.

Today most SD45T-2 and SD40T-2 are still widely in service in the US and other (mostly American) countries, only the SD45 (#7551 and #7549 in the accident) has been almost entirely retired, scrapped or rebuilt to SD40–2 specification (which involved replacing the V20-engine with a V16-unit).

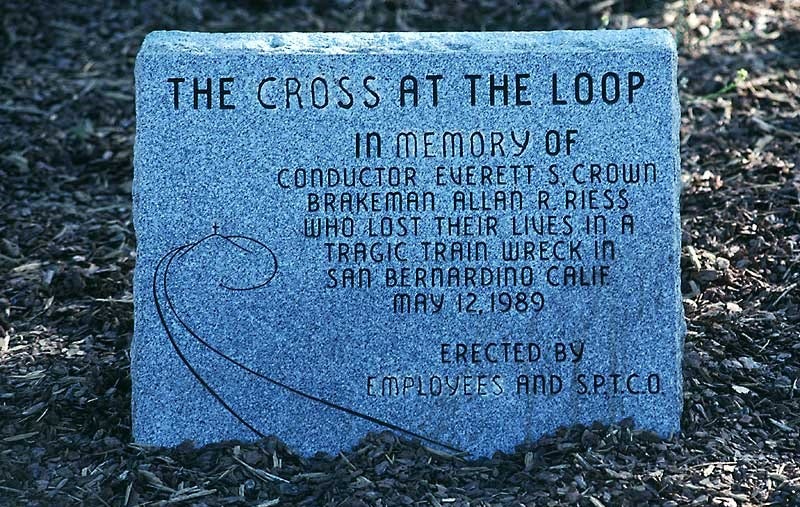

Shortly after the accident a Memorial was unveiled as a reminder of the accident, consisting of a large white cross as well as a memorial plaque and a marble bench facing the cross. Somewhat oddly the memorial wasn’t placed at the site but several miles up the route at the Tehachapi Loop, a 360° turn constructed to reduce the downhill gradient of the railway line. This puts the memorial 37km/23mi northwest of Mojave and a staggering 160km/99mi from the site of the accident (both measurements in linear distance). The site of the accident shows little sign of what took place, at most the large unkempt meadow on Duffy Street might make someone suspicious that something is off.

Video

The accident was the topic of Season 3 episode 9 of the Canadian TV-documentary series “Mayday”. As the show usually focuses on aviation accidents the episode ran under “Crash Scene Investigation” instead, premiering on the 30th of November 2005 with the title “Runaway Train” (which was changed to “Unstoppable Train” for US-airings). The episode features reenacted scenes along with footage of the aftermath and interviews with witnesses.

_______________________________________________________________