Background

Clapham Junction railway station is a train station in the Borough of Wandsworth, adjacent to the Borough of Clapham. Wandsworth is home to 329677 people (as of mid-2019), spread out over 34.26km²/13.23sq mi in the south of London, 6.5km/4mi southwest of downtown London and 38km/23.5mi north of Crawley (both measurements in linear distance).

Clapham Junction lies on the South West Main Line, a 230km/142mi single-to-quad-tracked electrified main line opening between 1838 and 1840. The line was built by the aptly named London and South Western Railway and connects various suburbs and towns between London and the town of Weymouth on the coast of the English Channel. The line is almost exclusively used for regional passenger services, with trains running at as much as 160kph/100mph (as of 2022)on the line, while the stretch ahead of Clapham Junction is a slightly slower zone.

The trains involved

The “Basingstoke” was a 12 car commuter train made up of three BR (British Rail) Class 423 (units 3033, 3119 and 3005) travelling from Basingstoke (hence the name) to London Waterloo station. Introduced into service in 1967 the Class 423 is a four-car electric multiple unit measuring 81.16m/266ft at a weight of 157.5 metric tons. They can carry up to 322 passengers in a two-class configuration at up to 145kph/90mph, and are distinguishable from similar trains by featuring an individual pair of exterior doors for every seating row.

The “Poole” (named after its usual departure, despite starting elsewhere on the day of the accident) was, similarly, a regional passenger service from Bournemouth to London Waterloo. It consisted of a BR Class 432 (number 2003) towing 2 4TC units (8027 and 8015). The class 432 is a four-car multiple unit introduced in 1966 alongside the Class 423. The motor cars are a new construction, while the unpowered cars were converted regular Mark 1 passenger cars. Each class 432 measures 78.8m/258.5ft in length at a weight of 175 metric tons and can carry up to 175 passengers in 3 classes at a speed of up to 145kph/90mph. They are easily distinguished from the class 423 by not having the uninterrupted row of doors down each side.

At the time of the accident BR Class 432 was pulling 2 Class 438 “4TC” units (8027 and 8015). The Class 438 had been introduced in 1966 and was a 3- or 4-car unpowered multiple unit constructed from retired mark 1 passenger cars, specifically made to be pulled by the class 432. They had no engines but did have a control cab for push-pull services. A 4-car set measured 78.7m/258ft in length at a weight of 134 metric tons and could carry up to 202 passengers in two classes.

The “Haslemere” was an empty Class 423 train consisting of units 3004 and 3425, leaving London southbound with only a driver and his assistant on board.

The accident

On the 12th of December 1988 Mister McClymont is approaching Clapham Junction at the controls of the 7:18am train from Basingstoke to London-Waterloo (referred to from here on as the “Basingstoke”), a 12-car train crowded with commuters. At approximately 8am he is approaching the signal WF138 at just over 97kph/60mph. Suddenly, with the train less than 28m/92ft from the signal, he sees the green light turn off as the signal jumps to red, ordering a stop. McClymont triggered an emergency stop, obviously speeding past the red signal, before realizing that the emergency stop would bring the train to a standstill short of the following signal (WF47) from where he intended to use a track-side telephone to report the incident. As such he eased up on the brakes as the train slowed, stopping in front of WF47 right as it turned from red to yellow (“proceed at caution”). He is sure that WF138 behind him has remained red as his train occupies the section beyond it, even after figuring out that it jumped to red without reason as there obviously was no train occupying the zone along with his. After coming to a stop McClymont exited his train and headed to two track-side telephones (the first one turns out to be out of service). However, as he reported a possible faulty red he was told that the system reported no such thing and that he had apparently stopped under a green signal.

As McClymont is on the phone with dispatch two trains are approaching his location. The “Poole” train was following behind McClymont’s Basingstoke at 97kph/60mph. Usually the Poole started at Poole station, but due to a minor derailment caused by vandalism it ran on a shortened connection on the day of the accident, having started at Bournemouth station a few kilometers down the line. Riding in the rear cab was Mister Flood, an off-duty train driver using the train to shuttle into London. He was watching the gauges out of habit, despite having gained a good skill in estimating train speeds during his lengthy career. The conductor on the Poole had taken a seat in his “office” in car 7, being unable to check the tickets as he had dropped his clippers between the train and platform at a previous stop.

Coming the other way out of London and also approaching Clapham Junction the day of the accident was the “Haslemere”, an empty train that was returning from dropping its load of commuters off at London-Waterloo. The driver aboard the Haslemere train would later report seeing the stopped Basingstoke train at WF47 with Mister McClymont at the telephone next to the tracks.

At 8:09am the Poole train is coming around a long left hand bend at approximately 80kph/50mph just south of Clapham Junction. The driver suddenly sees the fully stopped Basingstoke ahead of him and triggers an emergency stop, but the impending disaster is already unavoidable. At 8:11am, while McClymont is still on the phone, the Poole strikes the back of the stationary Basingstoke at approximately 56kph/35mph, ripping through the rearmost car as it’s deflected off to the right. The forces of the impact rip the Basingstoke’s rear car off the train and throw it several feet in the air, causing it to end up atop a 3m/10ft wall not far from Mister McClymont.

Moments earlier Mister Alston is passing the stopped Basingstoke in the empty Haslemere as he sees the Poole on the same track, instantly realizing the two trains are on a collision course. The Basingstoke and Poole collide just as the empty Haslemere comes level with the Basingstoke’s rear car. The Poole train running straight into the back of the Basingstoke train throws debris every which way, derailing the Haslemere train. Flying off its track to the right the Poole narrowly misses the cab of the oncoming Haslemere, dealing a glancing blow to the side of the empty train before continuing down the gap between the two trains, alternating between scraping along either train. Eventually the trains come to a stop with the remains of the Poole and the rear part of the Basingstoke jammed between the forward section of the latter and the stopped Haslemere, having largely turned into an unrecognizable heap of broken and bent wood and metal that fills the gap between the two other trains. In under a minute 35 people are dead and 484 are injured, 69 of which severely.

Aftermath

McClymont was still on the phone as the trains crashed a few feet from him, allowing him to immediately notify the signalman on the other end of the line of the accident and asking him to alert emergency services as casualties had to be expected. The signalman turned all surrounding signals that he had control over red and notified coworkers in adjacent signal boxes to do the same. However, he had no control over automatic signals along the line, leaving him unable to stop an approaching fourth train heading towards London. Driven by Mister Pike the fourth train received no indication of the obstruction ahead as WF138 showed yellow “proceed at caution” instead of red for “stop” despite two trains occupying its section. Pike was approximately 230m/755ft from the the faulty signal when he spotted the obstruction and managed to bring his train to a halt via an emergency stop, getting within 55m/180ft of the wreckage. Had there been another impact, even at slow speed, forcing the Poole forwards, it certainly would’ve had a catastrophic effect on survivors who were trapped in the mangled wreckage.

In the meantime Inspector Foster, a police officer who’d been riding aboard the Basingstoke, had run to the back of the train, assessing the situation and then run up to Mister McClymont. Realizing that the driver was not quite aware of the extend of what had happened Foster picked up the track-side phone himself and ordered the signalman again to send the emergency services, emphasizing that they were dealing with a major accident and required extensive support from the fire department and ambulance services. He also informed the signalman of the Haslemere’s involvement, something the signalman had been unaware of.

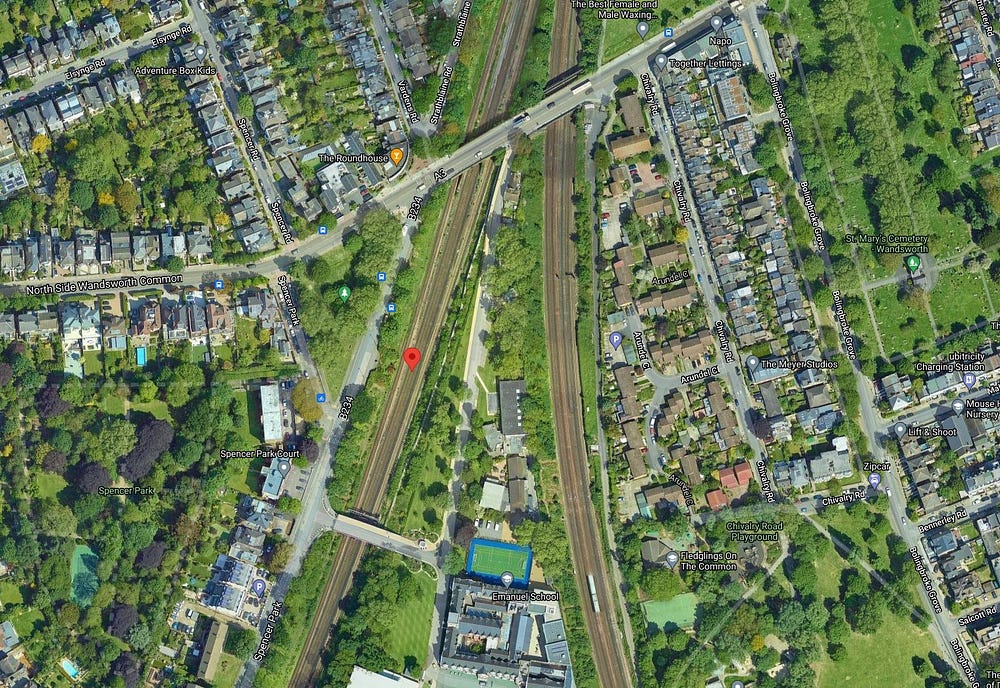

At the same time the deafening crash and dust rising from the cutting had motivated various local residents and passerby to call the emergency services and in some cases head to the site, where a group of students and teachers from the adjacent Emanuel School were the first outsiders to reach the wreckage followed by professional responders a few minutes later. Mister Stoppani, who had just turned 12 that day, later recalled hearing the crash and seeing “parts of a train” fly through the air outside the classroom window. Reaching the scene and climbing into one of the trains through a busted window he came upon a “pair of jeans with shoes on”, only realizing a few moments later that there was no upper body connected to the legs. In an interview he described a chaotic scene inside the train, with people screaming non-stop and being practically unable to talk or likely even comprehend where they were and what had happened. The students pulled survivors through the windows or tried to move pieces of the wreckage by hand while others tried calming trapped survivors, being unable to do much else until professional responders arrived.

Accessing the trains was difficult to say the least, requiring any responders to pass tall metal railings, a steep wooded embankment and a 3m/10ft high concrete wall. 1500 people were later estimated to have been aboard the trains, but the horrific scene the responders came upon left little hope for a lot of them. The leading cars of the Poole train had suffered the worst damage, with the leading car suffering a complete loss of interior space as it got obliterated between the two trains, essentially ceasing to exist. The second car, a buffet car, suffered extensive damage also, increased by the fact that the buffet cars’ seats were not bolted down at all. It’s unknown how many people had been aboard which train car, but it is assumed that the buffet car was nearly empty as the kitchen had been closed due to staff shortages. Mark 1 passenger cars were a 1930s design consisting of a very stiff frame with a rather lightweight body on top, so in an accident the cars tended to mount each other’s frames and slice through the weaker bodies, removing critical survival space.

Responders inched their way through the wreckage, soon bringing in a heavy duty crane to help pick the wreckage apart, continuously hoping to find survivors buried under pieces of the piled up wreckage. Rescue workers had to do delicate inch-by-inch work with tools and machinery meant to do anything but that, trying to avoid endangering or causing further suffering to trapped survivors. The adjacent Emanuel School was turned into a makeshift casualty center, offering enough space to separately collect the uninjured, injured and the dead and orchestrate their further treatment and transport. The report also specifically notes the use of a police helicopter to bring in doctors from further away when local resources were straining under the sudden high demand. Eight ambulances tirelessly shuttled survivors to hospitals before returning to the site for the next trip, while surgeons at local hospitals did their best to help those arriving there some survivors had to be operated on right by the side of the tracks before they could be carried up to the road, not to mention be driven to the hospital. One of the firemen on site recalls an incredibly sad scene, with Christmas cards strewn all over the wreckage as people had likely been writing them on the train to send them off later. The report notes that at least the weather and time of day were on the responders’ site, with the accident having happened on a clear and dry December day rather than in the rain or snow or at night. The last survivor wasn’t rescued from the wreckage until 1:04pm, 2.5 hours before the last victim was recovered.

Once the rescue and recovery of the passengers was finished the investigators took over the site, being tasked to find out how the hellish event could happen in the first place. An original suspicion that Mister McClymont had misread the signal as red was soon disproven as the signal had not properly reacted to both the Basingstoke and the Poole occupying its section of track post-accident either. Similarly, his decision to abort the emergency stop and bring the train to a halt at the next signal was proven to be in accordance with guidelines at the time. Knowing what we do now McClymont should have taken his train one signal beyond where he stopped, as WF47 was working properly it would have made the Poole stop behind the Basingstoke. However, there is no reasonable way such a decision could have been expected from Mister McClymont at the time. Narrowing down the cause of the accident to a continued faulty indication by signal WF138 the investigators started “chasing wires”, so the speak, suspecting a defect or wrong connection. Signal WF138 had just been installed/created under a month before the accident during the so-called Waterloo Area Resignalling Scheme, an extensive program to equip the area with new signals and wiring as the deteriorating condition of the existing equipment after 50+ years in service could not be ignored any longer. Signal WF138 had been installed/connected by 3 men, Mister Hemingway, his assistant Mister Dowd and their supervisor, Mister Bumstead. Once they completed their work it was to be tested and signed off on by an engineer, Mister Dray.

Most of the wiring-work was performed by Mister Bumstead and Dowd, with Hemingway having to do little but connect two new wires and disconnect an old wire. In simplified terms, instead of a wire running from a relay (TR DM) to a fuse the new wiring had a wire run from the same relay to a further relay (TR DL) and then from there to the fuse. TR DL was the track-circuit beyond the new signal, the new relay was tripped when a train went past the signal, turning WF138 red. Investigators found out that Hemingway had failed to disconnect the wire from the fuse end and, while it was disconnected from the relay it used to run to, he had not cut the wire back, insulated it or secured it away from the relay in any way, shape, or form (as in, he could’ve likely literally taped it down and been done, but didn’t). As it was the wire loosely “hung around” near its old contact to the relay, still long enough to technically connect to it should certain circumstances arise.

Two weeks after finishing work on the new signal, the day before the accident, Mister Hemingway was at work in the relay room of Clapham Junction’s signal box on an unrelated task with a different assistant. By coincidence he was working immediately to the left of TR DM and the new wiring that had been installed two weeks prior. The work involved changing the neighboring relay (TR DN), already creating a close vicinity to the lose wire that both should not be there and definitely shouldn’t be moved. The physical effort involved in Hemingway’s work on that day disturbed the new wiring, causing the improperly disconnected old wire to shift towards the relay TR DM, making metal-to-metal contact and creating a “shortcut” past TR DL. If a train passed WF138 and entered the “DL”-section of track it would trip the TR-DL relay, but due to the unintended connection the signal wouldn’t change as the relay TR DM fed directly to the fuse. The old wire would move randomly back and forth, connect and disconnect at any random time.

Nothing went wrong between 4am and 8am, as the trains always ran past the affected section with enough space between them. It was only when McClymont stopped his train in the affected section, having professional trust in the signal behind him being red, that the accident was unavoidable. WF138 hadn’t turned red as it should but was still showing “proceed”, with the lose wire having recontacted the relay and overridden TR DL, turning the signal green despite the train not only occupying the section but being parked in it. As it happened a loose, unintentionally half-connected wire, an unfinished job of maybe a minute long, caused death and destruction of catastrophic proportions. McClymont had seen the signal turn red (what he assumed was) early or very late and reacted accordingly, he had no way of knowing it would turn green again seconds later and send the Poole train into the rear of his train.

The investigation revealed that back in 1978 it had been decided that extensive resignalling was needed by 1986. However, the program was only approved by 1984 after three “wrong side signal failures” (a signal displaying the wrong command) were traced back to excessively aged equipment. On top of the six-year delay the program also had to make do with far less workers than intended, leading to employees feeling extremely pressured to work quickly and on an inflexible schedule which included supposedly voluntary overtime during weekends. When interviewing Mister Hemingway and examining his work in the previous weeks it came to light that he had worked seven-day weeks for the previous 13 weeks straight, almost certainly creating significant fatigue. Mister Dray had also not signed off on the work by the time of the accident, simply being behind schedule by over 2 weeks. Specifically, a simple wire-count that would’ve unveiled the old wire was not carried out, meaning the error would’ve only been discovered over two weeks after it had been put in place, with hundreds of trains passing the affected section in the meantime.

The report closes with no less than 93 recommendations, pointing out among other things a severe shortcomings in British Rail’s working practices, especially inadequate training, assessment, supervision, testing and, significantly, an incredible lack of understanding of the risks of signal failure. Also, it was deemed unacceptable that employees in safety-critical jobs (such as rewiring signals) were “voluntold” (told to do something supposedly voluntary) to work overtime, much less in such excessive amounts. Lastly, British Rail was told to install radios for communications between drivers and signal boxes in all trains that were expected to serve for five or more further years, removing the need to stop and go looking for a track-side phone.

British Rail was fined 250 thousand British Pound (equivalent to 550k GBP/300.8k Euros/341k USD in 2021) for breaching the 1974 Health and Safety at Work Act, while Mister Hemingway was not put on trial for his role in causing the accident. In 2007 the accident was one of the events cited in the creation of the new Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act, which allows a company as a whole to be charged with manslaughter or homicide rather than only individual employees.

Today a memorial stands on the sidewalk next to the tracks at the site of the accident, the gray stone is engraved with hands holding each other in front of a piece of track on one side while the other side reads:

For those who lost their lives in the Clapham Junction Rail Disaster on 12 December 1988. Those who were injured, their families, friends & all who helped & cared at the time & afterwards.

The last Class 423 units were withdrawn from service in November 2005, 10 years after the Class 432 had left British rails. Only a handful of the over 200 units made remain, some of which occasionally see use as historic trains. The series 438 unpowered units were retired back in 1989. A few Mark 1 passenger cars remain in service with private providers, often for historic tours, the last cars left main lines in 2005. Successive passenger car generations featured greatly improved structural engineering and thus crash safety, with the Mark 3 cars (introduced in 1975) showing a radical improvement already both in rigidity, rollover-avoidance and anti-climb design meant to reduce the risk of a passenger car mounting the adjacent car’s frame. A 2021 piece in an engineering magazine further notes that British train cars tend to be moved to slower and less frequented lines as they age, further reducing the consequences of a possible accident. Of course train cars remain at a structural disadvantage, having to be a large metal rectangle by design with the size-limit and capacity-requirements leaving little space for crash protection. Today the line through Clapham Junction is mostly served by Siemens Desiro-based BR Class 444, which, in regards to safety, are light years away from the relatively flimsy Mark 1 coaches.

Video

A BBC news report about the accident, which aired the night after the accident. WARNING: Some injured/bleeding people can be seen.

History repeats itself

On the 29th of December 2016 a train driver is departing Cardiff Central station in Wales when he sees two points ahead of his trains not being properly set for his route. The driver triggers an emergency stop and brings his train to a standstill ahead of the points, keeping it from ending up in the wrong track on a possible collision course. The area was in the process of a similar resignalling-process as Clapham Junction had been almost 30 years prior, and the points had been disconnected from the signaling system ahead of their scheduled removal. However, they had not been fixed in a specific configuration as they were intended to be due to a lack of planning and sufficient staffing leading to excessive work-hours and a testing-train being cancelled before the section was returned to service. A year later, on the 15th of August 2017, a passenger train was leaving London Waterloo station and ran into the side of a parked engineering train at low speed, causing material damage but thankfully no injuries. Here, the rushed installation of wiring had not been supervised or tested properly, causing the wrong setting of a set of points to go unnoticed as the feedback from the points wasn’t processed properly. The cause’s similarity to that of the Clapham Junction collision led the report to warn that apparently “some of the lessons from the 1988 Clapham Junction accident are fading from the railway industry’s collective memory”, which could have disastrous consequences.

_______________________________________________________________