Background

The Big Bayou Canot is a non-navigable sidearm of the Mobile River in Southwest Alabama, USA. At the site of the accident it’s just 130m/426.5ft wide, with shallow and muddy banks. Moving upstream it quickly looses more than half its width as it runs almost straight north (via various switchbacks) from there, creating a shortcut to a large bend in the Mobile River. It’s crossed by the Big Bayou Canot Bridge, a three-part bridge owned by CSX Transportation (the main freight train operator in the eastern United States), 15km/9.3mi north-northeast of Mobile (Alabama) and 85km/53mi west-northwest of Pensacola (Florida) (both measurements in linear distance).

At the time of the accident the bridge was used by both freight trains (mostly run by CSX, the owner of the bridge) and passenger trains, among them Amtrak’s Sunset Limited express train. The bridge carries a single track across the Big Bayou Canot, allowing trains to proceed towards Atmore (Alabama) to the northeast of the bridge without needing to go around the extensive wetlands all the way up north via Jackson (Alabama). Like its neighboring bridges across the Mobile River and Tensaw River the Big Bayou Canot Bridge was fitted with sensors to register the tracks breaking, meant to automatically stop trains in case of sabotage or a bridge collapse. The 80 years old bridge consisted of a 55m/180.5ft long truss bridge on the southwest bank and a 64m/210ft long wooden bridge on the northeast bank. Between the sections sat a 46m/151ft long steel girder bridge sitting on a sole central support column. Originally this section had been designed to swing open and allow boats to pass, but it had never received the equipment to move it. The section had also not been permanently connected to the other two sections, but an uninterrupted railway track had been laid across all three sections.

The vehicles involved

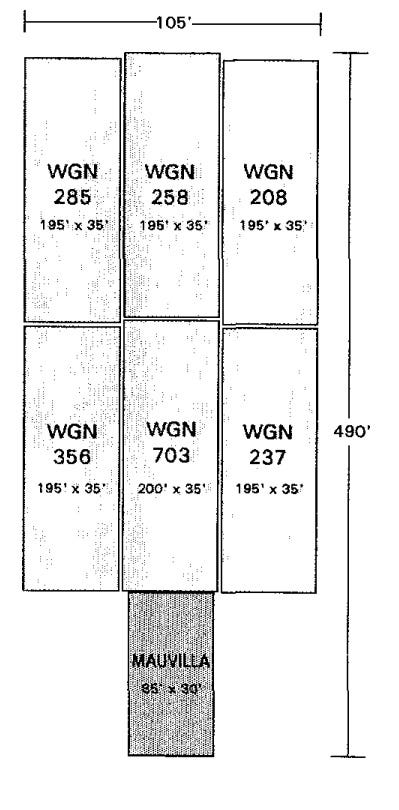

Moving northbound on Big Bayou Canot (where it had no business being in the first place) was a six-part barge-group (2 rows of 3 barges each) loaded with coal and raw iron. Pushing the unpowered barges was the towboat “Mauvilla”, owned by Warrior and Gulf Navigation, which had a radar system but no compass or maps on board. At the time of the accident it was under the control of Mister Odom, a relatively inexperienced pilot, who shared the boat with 2 deckhands and the captain.

Travelling eastbound across Alabama on its way from Los Angeles (California) to Miami (Florida) was Amtrak’s Sunset Limited Number 2, an overnight passenger express train regularly crossing the entire USA from the west coast to the east coast. The train consisted of seven passenger cars, a luggage car (recognizable by its roof being much lower than that of the remaining train) and three diesel locomotives. Leading the train was GE Genesis P40DC number 819, a four-axle diesel-electric passenger locomotive measuring 21m/69ft in length at 121.67 metric tons. The Genesis-series of locomotives is easily recognizable by featuring a sleek one box design opposed to the usual more “rugged” design of american diesel locomotives with a separate hood out front and walkways around the locomotive’s body. The Genisis-Series was constructed by General Electric following an inquiry by Amtrak looking for a relatively low (4.37m/14.4ft) locomotive capable of passing the low-profile tunnels on the northeast corridor. The streamlined design also aids the locomotives in their performance, allowing a top speed of 166kph/103mph. At the time of the accident Number 819 was just three months old, having been in service for 20 days.

Running behind the leading P40DC were two EMD F40 PH (numbered 262 and 312), a pair of four-axle 118 metric ton diesel locomotives introduced in 1975. Measuring 17.1m/56.2ft in length and 4.76m/15.8ft in height the F40PH was the predecessor to the P40DC, featuring a slightly streamlined but still more conventional design. Capable of 166kph/103mph their age certainly didn’t mean they slowed their more modern counterpart down when used together.

The accident

On the 22nd of September 1993 at 2:33am Sunset Limited Number 2 leaves Mobile station with 220 people on board, including the two conductors and 3 drivers (in the US called “engineers”). Among the passengers in the forward cars are Andrea Chancey, an 11 years old girl who suffers from Cerebral Palsy that leaves her dependent on a wheelchair, her adoptive parents, and Ken Ivory, a Texan oil worker who took the train because he missed a flight. Ivory was seated on the upper level of the second passenger car, the Chancey family was on the lower level of the same car. At the station a maintenance-crew performed repairs to an air conditioner unit and a toilet, causing a 30 minute delay. As the train leaves the city the surroundings are plunged into darkness, there are no light sources out in the woods and bush land around the river that could be seen even without the dense fog that settled in. At the same time Mister Odom, the pilot at the controls of the towboat, had erroneously turned into the Big Bayou Canot, thinking he was following Mobile River through a left turn a few hundred meters further upstream. Ships were banned from using the Canot, but lacking maps or a compass Odom didn’t know he was on the wrong river. With the fog getting thicker by the minute Odom soon couldn’t see the tip of the barges and chose to look for a tree on the bank to attach a rope to and wait for the fog to clear. He claims to have lowered his speed for this maneuver, but the exact speed of the ship is unknown. After two unsuccessful attempts to find a suitable tree with his searchlight Odom ordered the deckhands back to the towboat, fearing they might injure themselves in the darkness and fog or go overboard. He could see the two banks of the river tighten on his radar and, moments before impact, saw another object on his radar right in his path. Thinking that he was on Mobile River he figured the object to be another towboat he had let pass earlier. At 2:45am the right hand forward barge struck the center section of the bridge, knocking it out of alignment by approximately 91cm/3ft. As it was never fully equipped for swinging out of the way there were no sensors reporting the bridge’s movement, and the tracks on it severely kinked but didn’t snap, so the track-interruption sensors weren’t tripped. The lines on the right-hand pair of barges had snapped as it struck the bridge, causing it to fall behind the rest of the group by 24m/80ft, trapping the towboat against the bank of the river.

While the crew on the boat was still trying to figure out what had happened and where they were the Sunset Limited reached the bridge, travelling at 116kph/72mph under green signals. The leading locomotive struck the displaced bridge girder as it derailed, causing the center section of the bridge to collapse into the water as the locomotive drilled itself into the muddy bank until the forward 14m/46ft had disappeared into the mud. The driver was killed on impact without ever getting a chance to slow down or even know what happened. The second locomotive slammed into the wreckage of the first, starting a fire that consumed most of it and part of the leading locomotive. The third locomotive had all of its underside equipment (including wheels and fuel tanks) sheared off as it went into the water. Spilling diesel created a burning layer atop the water, illuminating the unfolding disaster for the witnesses. The baggage car and leading sleeper car were severely damaged as they struck the opposing bank before being consumed by the fire. Half of the following car and the entire third passenger car were submerged in the river. The rear 4 cars remained on the bridge, with the fourth car precariously dangling off the end as it came to a stop.

Aftermath

Back in the dining car towards the rear of the train the conductor picks himself up from the ground and radioes the drivers asking what happened, his calls remain unanswered. At 2:56am the conductor sends a mayday-signal to surrounding trains, one of which then contacts the shunting yard in Mobile, from where the mayday-signal is forwarded to the dispatch center in Jacksonville (Florida) and the Mobile Police Department. The phone number listed for the coast guard in Mobile’s directory turned out to contain errors, so initial attempts to reach them and aid in helping the stricken train fail. Meanwhile the mayday-call accidentally gets credited to the Mobile River Bridge, 5.1km/3.2mi linear distance north of the actual site. The lack of roads in the heavily wooded swampy area further slowed the response, responders wouldn’t come upon the wreckage until 3:20am. The responders headed to the site are faced with a unique problem as the area is only accessible by boat or train, and the accident destroyed the tracks and set the water on fire.

Meanwhile, in the second passenger car, Ivory and Chancey got knocked around as their car went into the water and struck the ground of the river, ending up half-submerged. As the train car comes to a rest Ivory goes to help passengers in the lower level of the car, fighting through ensuing chaos as people fight their way out of the water inside the car in near-darkness. The lights inside the train failed, the only light in the car comes from the burning diesel fuel floating on the river outside the windows. Ivory later recalls someone pushing Chancey up above the rising water, allowing him to grab her and pull her to safety. Chancey doesn’t recall who pushed her out of the water, it might have been one of her parents. She survives, but both her parents become part of the 47 victims. 103 people survive with injuries. Few people die from the crash itself, a lot of survivors succumb to fire and smoke inhalation while some fail to leave the sinking cars or can’t find somewhere outside the fire to surface and drown.

In the meantime the captain had relieved Odom of his duties, has the boat cut loose from the barges and carefully navigates it around the wreckage, pulling survivors out of the water and bringing them ashore. The assistant conductor eventually finds himself at the leading end of car 4 and manages to get some passengers to listen to him, they find the better swimmers among the survivors and organize a line to rescue less capable survivors and get them to shore. Among those who are rescued that way is Chancey, being handed down the line after being lifted out a broken window on the upper level of the mostly submerged car. Meanwhile the captain of the Mauvilla alternated between using his boat and a small skiff (a small paddleboat) to rescue survivors and returning to the shore to re-beach the floating barges so they wouldn’t endanger survivors, he had to repeatedly back off when the smoke filled the cabin of his boat. By 3:24am the coast guard, now almost at the site, requested assistance from any and all available boats in the area. One of the responding vessels was the Scott Pride, another towboat which managed to rescue 20 people from the water. By 4am the responders determined that there were no survivors, allowing the present fireboat to start focusing on extinguishing the flames. Eventually the fog lifted enough for two helicopters to help evacuating survivors, by 8:30 the last surviving passenger had left the site. Chancey finds herself at a hospital with minor injuries including oil inhalation, it’s only when relatives tell her the next day that she learns of her parents’ fate.

Initially investigators focus on Odom as the sole reason for the catastrophe, suspecting that he struck the bridge which caused a collapse. Was he distracted? Was he unfit to control a boat? But the more investigators look into the chain of events ahead of what ends up being the worst accident in Amtrak’s history the clearer it becomes that they can’t place sole blame on him. His confused nature found in the recorded radio calls after the accident simply came from him not knowing how he ran into something not meant to be on the river he thought he was travelling on. Investigators decided that the larger issue was that the bridge was arguably unfit for use, at the latest by the time uninterrupted tracks were laid across it the turning-mechanism should’ve been disabled. There was no permanent connection between the outer and center section of the bridge, which obviously played a major role in the events that unfolded. Furthermore, there were no lights on the bridge to warn any boats that might head down the Big Bayou Canot. Sure, there weren’t supposed to be any boats there, but when the bridge was planned there were obviously some expected, so why was there no system to let possible boats see the obstacle? This issue was adressed when the bridge was rebuilt, now being fitted with warning lights even if no boats were meant to go near it. The same upgrade was given to all bridges above waterways that could be used by a boat in the state. Also, bridges on rivers that had regular boat traffic were fitted with large, easy to recognize signs letting people identify their location easier in the case of an accident. The fact that, initially, no one knew exactly where they were/what bridge they were at had significantly slowed down the response.

The next issue to adress was the poor equipment of the Mauvilla, it was perfectly legal for the boat to operate even in darkness and fog without maps or a compass on board, leading to Odom getting lost among the various rivers and sidearms. This error was a major part of the chain of events leading up to the accident, aided by Odom not being trained in the usage of the radar, leading to him initially confusing the bridge’s radar signature for another boat. Following the accident it was made mandatory for all boats wanting to use the Mobile River to carry radar, maps and a compass. It is also now illegal to give control of a vessel in the are to a person not sufficiently trained in the usage of radar. Investigators furthermore criticized Amtrak’s lack of a record of the passengers on each train which prolonged the rescue/recovery effort and delayed firefighting at the site. To combat this in the future Amtrak introduced electronic records of passengers for each of their trains. While charges were initially filed against Odom he was eventually declared not guilty, but he still chose to never assume control of a ship again. In the end there were no legal consequences for anyone involved in the accidents, although it did shine a light on the poor safety state of some American railroads.

The leading locomotive had been pretty much new at the time of the accident and was the first of its kind to be written off, as was most of the forward part of the train. The half-submerged car Ivory and Chancey had been in was refurbished and returned to service, as were the cars from car 4 to the back of the train. The bridge was rebuilt after the accident in nearly the same configuration, and initially service on the rail line in the area continued the way it had run before the accident. In 2005 Hurricane Katrina caused extensive damage from floods and winds to the local railway infrastructure, including flooding of Mobile’s train station. Following the accident Amtrak cut the route of the Sunset Limited short, now terminating at New Orleans instead of continuing out to Florida. Reintroduction of passenger service to Mobile and perhaps eventually all the way to Florida was announced for January 2022 with Amtrak footing the bill for needed repairs and construction.

In a 2018 interview both Chancey and Ivory said that they don’t blame Odom for what happened, that they don’t hold a grudge against him. In fact it’s quite the opposite, with Chancey expressing concern about him, how he handles the events of the night. Chancey blames Amtrak and CSX Transportation, saying the sorry state of the bridge was the main factor to blame for the accident. An intact, static bridge could have taken the impact by the barge without causing a derailment. Chancey says she still gets reminded of the accident whenever she hears of another Amtrak train derailing, which, in her words, has happened way too often since the accident. She declined to visit the site for a memorial service in 2016, and also has never been to Mobile to see the memorial plaque. Ivory notes only one lasting change, he has never taken a train since the accident, preferring flights or to just drive.

Video

In 2004 National Geographic examines the accident for the first season of their “Seconds from Disaster”-series. It’s during the research for the accident that a cruel coincidence is revealed: Unscheduled repairs to the toilet and air conditioning delayed the train by 30 minutes. Had the train not needed those repairs, or had they been delayed to the next station, the Sunset Limited would’ve passed the bridge just fine a little over 20 minutes before the barge struck the bridge.

_______________________________________________________________